Gaudí’s buildings are immediately recognizable, but what makes them distinctive is not stylistic quirk. It is a coherent philosophy applied with obsessive precision. To understand Gaudí requires learning how he thought about architecture, materials, and the relationship between form and function. The buildings make far more sense once you grasp his underlying principles.

The Origins of His Method

Gaudi had a famous claim: “Originality consists in returning to the origin.” He was not being poetic. He meant that architecture should study nature’s solutions to problems. Nature does not use straight lines because they are inefficient. Nature does not apply decoration randomly. Every curve, every angle, every material choice serves a structural or functional purpose.

This came from his background. Growing up in a family of coppersmiths, he watched craftsmen understand materials through years of handling them. You cannot work iron effectively without understanding its properties. You cannot shape copper without respect for its nature. This craftsman’s knowledge never left him. He approached architecture the same way: understand the material, understand the forces acting upon it, then design accordingly.

When Gaudi visited building sites, he brought a measuring tape but also observation. He watched how light moved across surfaces at different times of day. He studied how water drained. He noted where wind created eddies. These observations informed design. Form was not applied to structure. Form was the result of allowing structure to express itself honestly.

This explains why his buildings look organic. They are not stylistically trying to mimic nature. They are functionally designed according to principles nature uses. The resemblance is not coincidence but consequence.

Trencadis and the Language of Broken Tiles

Walk around any Gaudi building and you encounter fragmented ceramic tile in patterns that seem chaotic until you begin to see their logic. This technique is called trencadis. It translates roughly as “broken pieces,” but it is far more sophisticated than decorative mosaic.

Gaudi did not invent trencadis, but he elevated it from craft to structural language. Here is why it mattered to him: ceramic waste from tile factories was essentially free. Poor neighborhoods in Barcelona produced broken tiles constantly. Rather than seeing this as waste, Gaudio saw it as material. The colour variations in discarded tile were not problems but resources.

Trencadis allowed Gaudio to achieve colour without applying paint or coloured tile in uniform patterns. The broken fragments, arranged deliberately, created surfaces that caught light differently depending on viewing angle and time of day. A surface that appears one colour at noon looks entirely different at sunset. The colours are distributed to balance weight visually. What appears random is actually calculated.

This had another virtue: trencadis was durable. Because the tiles are ceramic, they resist weathering. Because they are irregular, water does not pool in patterns that erode faster. And because Gaudio employed the same craftsmen repeatedly, developing consistent standards, the work maintains integrity over decades.

Study the trencadis closely on Park Güell’s famous serpent bench or on Casa Batllo’s facade. You will see that colours are not randomly placed. Blues and greens cluster in ways that create visual movement. Warm tones appear at joints to guide your eye. The composition is careful even though the individual fragments are haphazard. This synthesis of accident and intention is quintessentially Gaudio.

The Mathematics of Curves

Gaudí did not use flat surfaces or simple right angles. His buildings employ parabolas, hyperbolas, hyperboloids, catenary arches, and complex ruled surfaces. This was not stylistic choice. It was structural necessity.

A catenary is the curve a chain or cable assumes when hung between two points. Gaudí studied this shape obsessively because it distributes load perfectly. If you invert a catenary and use it as an arch, it requires no additional support. A traditional arch requires flying buttresses and external bracing. A catenary arch, inverted, supports itself through geometry.

This allowed Gaudí to eliminate the visual clutter of external buttressing. The Sagrada Familia’s interior demonstrates this principle. Massive columns support vaults through angled forms derived from catenary geometry. The forces flow through the structure without need for external bracing. The interior feels open because it is structurally open.

His use of hyperboloid forms served similar purposes. A hyperboloid can be created by rotating a straight line around an axis. This means hyperboloid structures can be assembled from straight elements (easier to manufacture and transport) while creating curved surfaces (better for distributing forces and creating visual interest). On Casa Mila’s facade, the undulating form is not merely beautiful. It distributes wind loads more effectively than a flat surface would.

Computer analysis later revealed that Gaudí had achieved structural efficiency that modern engineers considered optimal. He did this not through calculations but through physical models and intuitive understanding of geometry and materials. He would build plaster models, test them with weights and strings, observe where they failed, and modify. This iterative method anticipated modern computational design by nearly a century.

Visiting Gaudí's Masterworks

Most visitors follow a predictable circuit: Sagrada Família, Park Güell, Casa Batlló, Casa Milà. These are essential, but the standard tourist approach means experiencing them in crowds, often with time pressure. A better strategy involves understanding Barcelona’s geography and pacing your visits thoughtfully.

The city’s Gaudí sites cluster in specific zones. The Eixample district contains Casa Batlló and Casa Milà along Passeig de Gràcia. Sagrada Família stands northeast of the Eixample. Park Güell occupies the northern hills. Rather than a single day of rushing, consider a multi-day approach focused on different neighborhoods.

Day One: Passeig de Gràcia and the Early City

Day One could concentrate on Passeig de Gràcia. Start at Casa Batlló and arrive at opening time if possible, as morning light clarifies the facade’s colour and form. Spend at least an hour inside. Gaudí designed the apartments as practical dwellings, and understanding how rooms flow, how light enters, and how materials work transforms abstract appreciation into concrete understanding. You realize his innovations solved real problems.

From there, walk to Casa Milà. The rooftop is extraordinary. The city views are superb, but more importantly, you see the building’s structural logic from above.

Afternoon should include Palau Güell, a short walk along Carrer Nou de la Rambla. This palace, designed for Eusebi Güell, represents Gaudí’s work before his most radical period. It is less visited than other properties but architecturally sophisticated. The entrance demonstrates Gaudí’s approach to metalwork. The interior courtyard creates climate control through form. Few tourists see it, which means you can experience the spaces without crowds.

Day Two: Sagrada Família

Day Two focuses on Sagrada Família. This requires careful planning. It’s advisable to book tickets well in advance for early morning entry. The light in morning hours illuminates the interior in a way that afternoon cannot match. The stained glass shows its colours against natural light rather than artificial fluorescence.

Take the audio guide or book a small group tour. The building’s symbolism is complex, and a guide or audio explanation helps you understand what you are seeing structurally and spiritually. Allow at least two hours as a minimum.

Day Three: Park Güell and Gaudí’s Domestic World

Day Three addresses Park Güell. The challenge is crowds. Early arrival is essential. Book tickets with an early time slot, around 9:30 a.m. if possible. Arrive at the main entrance via Carrer d’Olot, where the famous dragon gateway stands. The entrance sets the aesthetic tone.

Spend time in the monumental area studying the serpent bench, the viaducts, and the light filtering through the columned walkways. Then venture beyond the ticketed zone into the free areas where locals gather. See how Gaudí’s architectural language transitions from formal design to landscape integration.

Visit the Gaudí House Museum if time permits. He lived in this modest building from 1906 until 1925. It contains his furniture and personal effects and provides context for understanding him as a person rather than merely an architect. The simplicity of his living conditions contrasts sharply with the luxury his clients demanded and the grandeur his buildings achieved.

Practical Considerations

Practical considerations matter. Barcelona’s metro is efficient, but Park Güell requires uphill walking from the nearest stations. Bus 24 from Plaça Catalunya reaches the park entrance more directly. Wear comfortable shoes. The Eixample’s blocks are manageable on foot, but Park Güell involves noticeable elevation change. Consider timing visits to avoid intense midday heat in summer.

Weather affects the experience substantially. Early morning or late afternoon light transforms facade colours on Casa Batlló and Casa Milà. Rain changes how the trencadis reads. Visiting twice in different seasons or at different times of day provides entirely different experiences.

Photographs online do not prepare you for the actual scale of these buildings. Sagrada Família is far larger than images suggest. Casa Batlló’s facade is more complex. Park Güell occupies more territory than most visitors expect. Budget more time than you think necessary. Rushing through Gaudí defeats the purpose of visiting.

Beyond the Famous Sites

Most visitors miss several important works. Casa Vicens, Gaudí’s first major commission, demonstrates his early orientalist period. It sits on Carrer de les Carolines in the Gracia neighborhood. The ceramic work is extraordinary, and because it is not on the standard tourist route, you experience it without crowds.

The crypt of the Colonia Güell, outside Barcelona in Santa Coloma de Cervelló, is worth a day trip if you have time. This church crypt served as Gaudí’s laboratory for forms and techniques he later used on the Sagrada Familia. It is smaller and more intimate, allowing clearer understanding of his structural innovations. The journey by train and bus requires planning, but serious Gaudí students should visit.

Torre Bellesguard, another overlooked work, sits on the hills north of Barcelona. Gaudí designed this neo-Gothic tower around 1900. It represents his engagement with historical architecture filtered through his distinctive vision. The interior courtyard and the view across Barcelona make it worth seeking out.

Why Gaudí Matters Now

The world has changed since Gaudí’s death in 1926. We have digital tools he never imagined. We understand building codes and safety standards he worked without. We have industrial efficiency he could not access. Yet his principles remain valid. Structural form emerging from honest engagement with materials. Ornament serving purpose rather than decoration.

Materials used for what they intrinsically are rather than disguised as something else. Integration with natural and urban landscape. These concerns matter more now than when he lived.

Gaudí did not design for immediate visual impact. He designed for buildings to age well, for them to remain functional and beautiful, for them to reward careful looking over many visits. In an era of disposable architecture designed for quick photographs, his commitment to durability and depth feels increasingly precious.

Visiting Gaudí’s Barcelona is not tourism. It is education. You encounter someone who thought carefully about how humans live in built environments and who used architecture as a language to express spiritual and cultural values. The buildings are beautiful, but their beauty is inseparable from their intelligence. Understanding that intelligence requires time, attention, and willingness to learn how Gaudí thought.

Ready to explore Gaudí’s Barcelona with clarity and ease? Speak with Do Not Disturb to curate a journey that brings his architecture to life.

Related destinations

Suggested articles

How to Plan the Perfect Luxury Trip to Angkor Wat

A Guide to Sri Lanka’s Tea Plantations

The Maldives Fixed Its Arrival Problem: Inside the New Velana Airport

The Best Islands in Australia for a Luxury Beach Holiday

How to Plan a Luxury Australian Outback Experience

A Luxury Guide to Australia’s Wine Regions

How to Plan a Luxury Trip to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef

The Best Luxury Hotels in Seychelles

Best Caribbean Islands for Private Jet Travellers

Island-Hopping in the Caribbean: The Best Routes for a Luxury Trip

Santorini or Mykonos: How to Choose the Best Greek Island for You

The Athens Riviera: Greece’s Glamorous Coastline Beyond the Islands

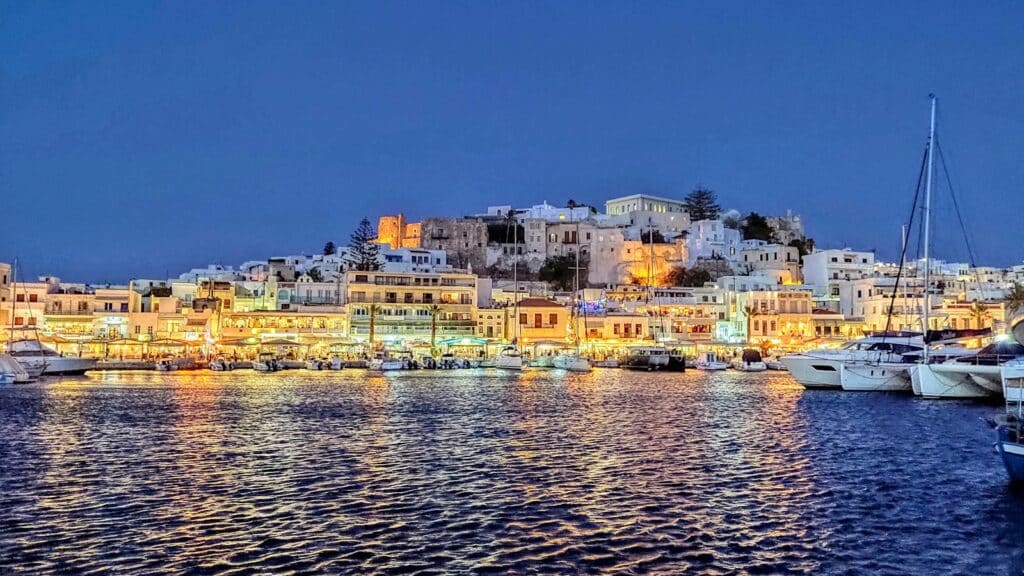

Paros: The Greek Island Stealing Attention from Mykonos and Santorini