The Great Barrier Reef exists at a scale that defies comprehension. Stretching 2,300 kilometers along Australia’s northeastern coast, visible from space, comprising nearly 3,000 individual reef systems and 900 islands, it represents the largest living structure on Earth. What follows is a guide to experiencing it properly.

The reef begins where most tourists stop looking. The popular pontoons anchored off Cairns and Port Douglas provide encounters with coral and fish, but they float above the reef’s busy margin, its most accessible and therefore most visited edge. Beyond this zone, stretching across a marine park larger than Italy, lie outer reefs where the coral grows in cathedral formations, ribbon reefs where pelagic species patrol the drop-offs, and islands so remote that the only footprints on their beaches belong to nesting turtles.

Accessing this deeper reef requires either a liveaboard vessel or a base on one of the islands scattered across the marine park. Both approaches have merit. Liveaboards cover distance, moving between dive sites that land-based visitors cannot reach.

Island resorts provide comfort and variety, their locations enabling day trips to surrounding reefs while offering beaches, bushwalking, and the particular pleasure of waking up inside the ecosystem you’ve come to explore.

Understanding the Reef's Geography

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park divides roughly into three sections, each with distinct character and access considerations.

The Northern Reef, from Cape York to Cooktown, remains the least developed and most pristine. Lizard Island, the region’s sole luxury option, provides access to some of the reef’s most spectacular diving, including the famous Cod Hole where giant potato cod have been interacting with divers for decades. The remoteness here is genuine: Lizard lies 240 kilometers north of Cairns, accessible only by private charter flight.

The Central Reef, from Cairns to the Whitsundays, sees the most visitor traffic but also offers the most options. The outer ribbon reefs, accessible by liveaboard from Cairns, provide wall diving and pelagic encounters that the inner reefs cannot match. The islands here range from backpacker havens to genuine luxury, with the Whitsundays in particular offering a concentration of high-end options.

The Southern Reef, from the Whitsundays to Bundaberg, includes Lady Elliot Island and Heron Island, both significant for their direct reef access. These coral cays sit directly on the reef itself, eliminating the boat travel required at other destinations. You can walk from your room into the water and find yourself swimming over coral gardens within minutes.

Each section experiences the reef differently. Northern waters tend toward greater clarity and more dramatic underwater topography. Central reefs offer variety and accessibility. Southern sites provide the unique experience of staying on the reef itself. Understanding these distinctions helps match expectations to destination.

When to Visit

The Great Barrier Reef spans 14 degrees of latitude, and conditions vary accordingly. Generally, the Australian winter (June through October) provides the most reliable conditions: calmer seas, excellent visibility, comfortable temperatures, and minimal rainfall. This period also coincides with the southern humpback whale migration, adding megafauna encounters to the reef’s resident attractions.

The Australian summer (December through February) brings warmer water temperatures and the possibility of coral spawning, an extraordinary annual event when the reef reproduces in a synchronized mass release of eggs and sperm. However, summer also means cyclone risk in northern regions, occasional box jellyfish presence (requiring stinger suits for water activities), and reduced visibility following wet season rainfall.

The shoulder months of November and May often provide excellent conditions with fewer visitors, though weather becomes less predictable. Water temperature remains comfortable year-round, ranging from 24°C in winter to 29°C in summer, meaning diving and snorkeling suit any season for those willing to accept variable conditions.

For minke whale encounters, June and July bring these curious creatures to the ribbon reefs, where they often approach snorkelers with an inquisitiveness that distinguishes them from more cautious whale species. This brief window has become a pilgrimage for marine life enthusiasts, and liveaboard expeditions during this period book months in advance.

Getting There

International visitors typically arrive via Sydney, Melbourne, or Brisbane, connecting onward to Cairns or the Whitsunday Coast (Proserpine/Hamilton Island airports). Cairns functions as the primary gateway for northern and central reef access, its airport handling direct flights from major Australian cities and selected international routes from Asia and the Pacific.

Hamilton Island, in the Whitsundays, offers an alternative entry point with direct flights from Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane. The island’s airport (the only commercial airport on a Great Barrier Reef island) provides immediate access to the Whitsunday region without the ground transfers required from Proserpine on the mainland.

From these hubs, access to specific destinations varies. Lizard Island requires a private charter flight from Cairns, the 60-minute journey providing aerial perspectives of the reef that justify the expense. Orpheus Island operates helicopter and seaplane transfers. Heron Island relies on a combination of flight to Gladstone and launch transfer. Hayman Island connects via a luxury yacht transfer from Hamilton Island.

The transfers themselves often constitute highlights rather than inconveniences. Flying low over the reef reveals its structure in ways that water-level perspectives cannot: the dark blue of deep channels, the aquamarine of shallow lagoons, the brown and purple of healthy coral visible through crystalline water. Travellers focused solely on reaching their destination miss half the experience.

Lizard Island

Lizard Island occupies the pinnacle of Australian reef luxury. This 1,000-hectare national park island, the northernmost resort on the Great Barrier Reef, hosts a single property: 40 suites and villas scattered along beaches that would be famous anywhere but here compete with two dozen others equally spectacular. The resort operates on all-inclusive terms, with gourmet dining, premium beverages, and non-motorized water sports included in rates that rank among Australia’s highest.

The location provides access to what many consider the reef’s finest diving. The Cod Hole, 20 kilometers distant, delivers reliable encounters with the giant potato cod that have made this site famous. Osprey Reef, further offshore, adds shark encounters and dramatic wall diving. Closer to the island, the reef systems surrounding Lizard itself offer excellent snorkeling directly from the beach, with fringing reefs accessible without boat travel.

Beyond the water, Lizard offers bushwalking to Cook’s Look (where Captain Cook surveyed his passage through the reef in 1770), pristine beaches accessible only to guests, and the research station whose scientists have studied the reef for decades.

Qualia, Hamilton Island

Qualia approaches reef luxury from a different angle. This adults-only property, occupying the northern tip of Hamilton Island, provides 60 pavilions positioned for privacy and views across the Whitsunday Passage. The design channels contemporary Australian architecture: clean lines, natural materials, floor-to-ceiling glass framing the surrounding waters.

The reef here lies further offshore than at Lizard or Heron, requiring boat excursions to reach quality snorkeling and diving. The resort operates its own vessels, with trips to the outer reef, Whitehaven Beach, and surrounding islands departing regularly.

Hardy Reef’s pontoon, while shared with day-trippers from the mainland, provides reliable coral and fish encounters, and private charter options eliminate the crowds entirely.

Orpheus Island Lodge

Orpheus Island operates at a different scale. This 11-room property occupies a continental island (granite rather than coral) surrounded by fringing reefs and positioned within the marine park’s protected zones. With a maximum of 28 guests, you’ll encounter the same faces at dinner, recognize the staff by name within hours, and experience a house-party atmosphere that larger resorts cannot replicate.

The reef access here is exceptional. The island’s fringing reefs begin steps from the beach, their shallow waters suitable for snorkelers of any experience level. Boat trips reach outer reef sites where the coral formations and fish diversity increase dramatically. The resort’s location, away from major population centers and the day-trip circuits they generate, means even popular sites feel uncrowded.

Orpheus includes all meals, beverages, and most activities in its rates. The dining emphasizes local seafood and produce, with set menus that change daily. The atmosphere trends romantic, attracting honeymooners and couples seeking seclusion. Families with children under 15 are not accommodated, ensuring the tranquility that defines the property.

Heron Island

Heron Island provides something no other Great Barrier Reef resort can match: you sleep on the reef itself. This coral cay, 72 kilometers off the Queensland coast, sits directly atop the reef platform, meaning snorkeling and diving begin at the beach rather than requiring boat travel. The experience of walking into waist-deep water and finding yourself surrounded by coral and fish within meters is unique among Australian reef destinations.

The resort, operated by Aldesta Hotels, offers accommodation ranging from comfortable reef rooms to more spacious point suites with ocean views. The facilities are more modest than Lizard or qualia, with an atmosphere that trends toward eco-lodge rather than luxury resort. What you sacrifice in polish you gain in access: multiple daily dives, unlimited beach snorkeling, guided reef walks at low tide, and the extraordinary experience of nesting turtle encounters (November through March) when green and loggerhead turtles haul themselves onto the beach mere meters from your room.

The University of Queensland operates a research station on Heron, and guests can engage with scientists studying the reef’s ecology. This proximity to active research adds dimension to the visitor experience, connecting leisure travel to the conservation questions that increasingly shadow reef tourism.

Experiences Beyond Diving

The reef rewards attention even if you never submerge. Snorkeling provides access to the same ecosystems divers explore, with shallow reef systems often supporting greater fish diversity than deeper sites. Many visitors discover that snorkeling delivers equivalent wonder without the certification, equipment, and ascent limitations that diving requires.

Scenic flights reveal the reef’s structure from perspectives impossible at water level. Helicopter and seaplane tours from Cairns, Port Douglas, and the Whitsundays provide aerial views of the Heart Reef (a naturally occurring heart-shaped coral formation), the Great Barrier Reef’s outer edge, and the contrast between reef systems and the deep blue of the Coral Sea beyond.

Glass-bottom boats and semi-submersibles offer reef viewing for those preferring to stay dry. While these experiences lack the immersion of swimming, they provide genuine encounters with coral and fish, particularly valuable for non-swimmers or visitors with mobility considerations.

Indigenous cultural experiences increasingly complement reef visits. Traditional owners have maintained connections to reef country for tens of thousands of years, and operators now offer opportunities to learn about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relationships with the marine environment. These perspectives add cultural depth to natural history, contextualizing the reef within human as well as geological time.

The Conservation Conversation

Any discussion of Great Barrier Reef travel must acknowledge the reef’s challenges. Climate change, manifesting primarily through marine heatwaves that cause coral bleaching, has significantly impacted reef health over recent decades. The 2016, 2017, 2020, and 2022 bleaching events caused widespread coral mortality, particularly in northern sections.

Yet the reef retains extraordinary vitality. Coral recovery has been faster than predicted in many areas. Fish populations remain abundant. The diversity of reef systems means that while some sections suffer, others thrive.

Lizard Island supports research initiatives. Heron Island hosts university scientists whose work directly informs reef management. Many properties contribute to citizen science programs, engaging guests in data collection that supplements professional monitoring.

The ethics of reef tourism generate legitimate debate. Travel contributes to the emissions driving climate change, yet tourism revenue funds conservation work and provides economic alternatives to extractive industries. Each visitor must navigate this tension personally. What seems clear is that visiting the reef, experiencing its wonder firsthand, creates advocates for its protection in ways that documentary footage cannot replicate.

The Case for Going

The Great Barrier Reef’s long-term future is debated, but its present remains astonishing. Coral walls still glow with colour, fish swirl in thick shoals, and encounters with reef sharks, manta rays or even dugongs happen more often than visitors expect. Headlines about bleaching rarely reflect the full reality: the reef is vast, varied, and often far healthier than the global narrative suggests.

Luxury travel simply improves the access. It brings you to outer reefs where coral cover is strongest, and to islands where visitor numbers stay low. It gives you time in the water when the reef feels most alive, drifting over bommies packed with movement and realizing just how complex this ecosystem really is. These moments are still very much possible for travellers willing to make the journey.

The reef asks for awareness and respect, and rewards it with experiences found nowhere else on Earth. And as the region’s lodges and island retreats continue to evolve, the combination of world-class marine encounters and high-end comfort feels more compelling than ever.

Plan your Great Barrier Reef journey with Do Not Disturb. Whether you’re drawn to Lizard Island, a liveaboard diving expedition, or a trip that combines reef and rainforest, our travel experts craft journeys tailored to you. Get in touch to start planning.

Suggested articles

A Guide to Sri Lanka’s Tea Plantations

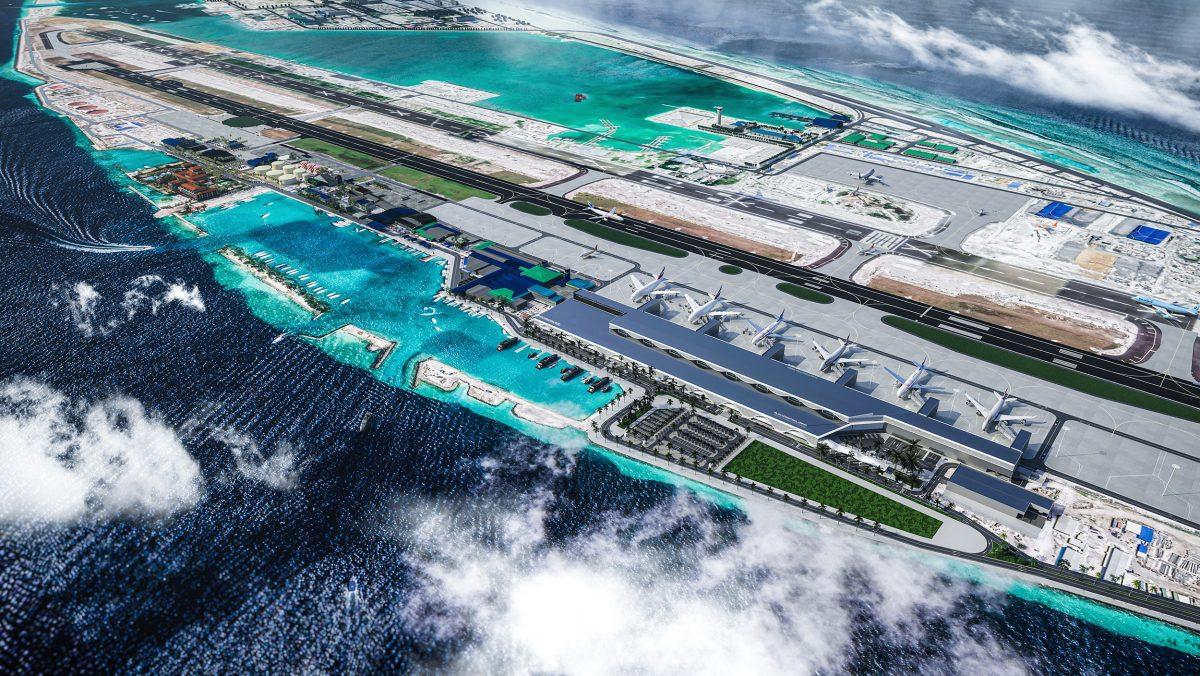

The Maldives Fixed Its Arrival Problem: Inside the New Velana Airport

The Best Islands in Australia for a Luxury Beach Holiday

How to Plan a Luxury Australian Outback Experience

A Luxury Guide to Australia’s Wine Regions

The Best Luxury Hotels in Seychelles

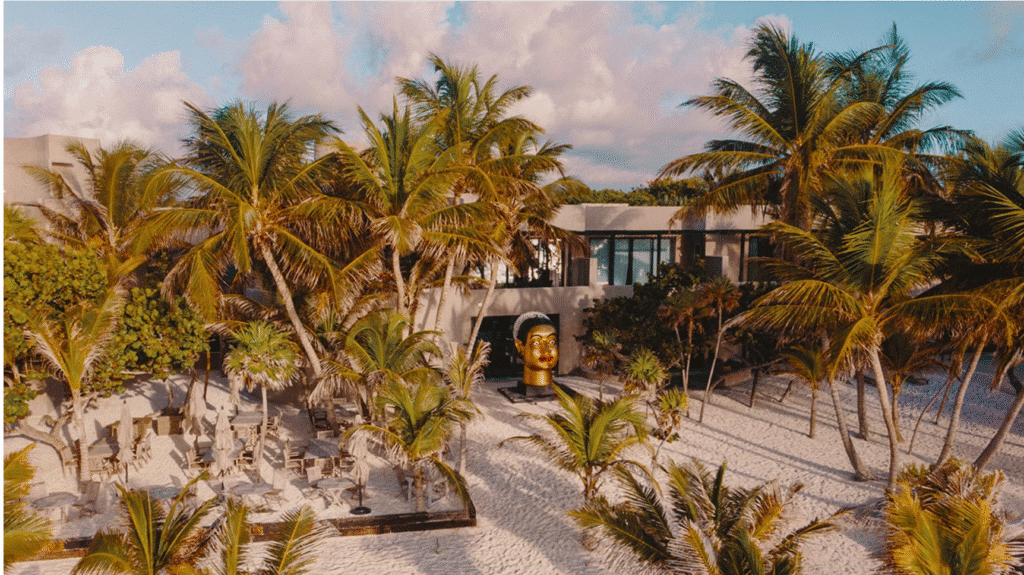

Best Caribbean Islands for Private Jet Travellers

Island-Hopping in the Caribbean: The Best Routes for a Luxury Trip

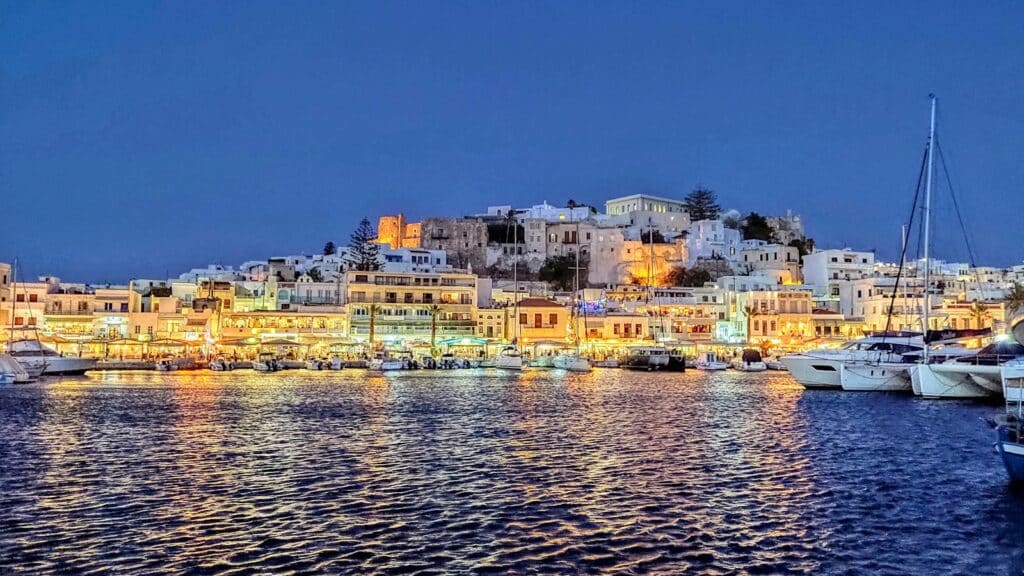

Santorini or Mykonos: How to Choose the Best Greek Island for You

The Athens Riviera: Greece’s Glamorous Coastline Beyond the Islands

Paros: The Greek Island Stealing Attention from Mykonos and Santorini

The Best Greek Islands for Luxury Travel: How to Choose the Right One

Exploring Mayan Culture in the Riviera Maya: From Chichen Itza to Tulum