Before it became synonymous with yachts and cinema, the French Riviera was a quiet coastline prescribed for winter health. Over two centuries, it evolved into the world’s most enduring symbol of luxury travel.

The transformation of a remote Mediterranean coastline into the world’s ultimate high society destination represents one of tourism’s most remarkable evolutions. The French Riviera (or Côte d’Azur, as it has been known since 1887) emerged through a precise sequence: medical prescription, royal endorsement, railway revolution, and cultural reinvention.

What began as Victorian winter health therapy evolved into Jazz Age summer hedonism, then Hollywood glamor, establishing a mythology of luxury that persists despite mass tourism’s arrival.

The essential paradox: the Riviera succeeded by convincing successive generations of elites that its pleasures remained exclusive even as accessibility expanded. Each wave believed itself pioneering, yet each built upon foundations laid by previous arrivals.

Victorian Medicine Prescribed Sunshine

The Riviera’s aristocratic colonization began with tuberculosis, which claimed countless Victorian lives in England’s damp, polluted cities. Scottish surgeon Tobias Smollett published “Travels through France and Italy” in 1766 following his 18-month Nice sojourn, documenting how warm winter climate cured his TB. His meticulous weather records lent medical authority to travel writing.

Scottish doctor John Brown popularized “climato-therapy,” prescribing climate change to cure diseases. Wealthy British patients began wintering along the Côte d’Azur, escaping England’s brutal cold for Mediterranean mildness. Nice, then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia rather than France, offered exotic foreignness with Italian architecture and sufficient infrastructure.

Lord Henry Brougham discovered Cannes in the mid-19th century and transformed it from fishing village to elegant resort through patronage. Queen Victoria visited in 1882, returning eight times and recommending the region to her extensive social network (which encompassed all of European royalty and the highest echelons of high society). Her endorsement opened floodgates. By the 1880s, Guy de Maupassant observed: “Des princes, des princes, partout des princes.”

The 1864 railway completion made Nice accessible to all Europe. One hundred thousand visitors arrived in 1865. By 1874, foreign residents in Nice, predominantly British, numbered 25,000. Writer Stéphan Liégeard coined “Côte d’Azur” in his December 1887 book, adapting his birthplace name Côte-d’Or by substituting azure Mediterranean for Burgundy’s gold.

Trips we recommend...

Belle Époque Grandeur Built Theatrical Stages

The period from 1890 to 1914 crystallized the Riviera’s architectural and cultural identity. Prince Charles III of Monaco constructed a casino in 1856, calling it a “health spa” to avoid church opposition. His agreement with François Blanc, the French businessman who succeeded at Baden-Baden, transformed prospects. The settlement around the casino was named Monte-Carlo in the prince’s honor.

In 1878-79, architect Charles Garnier (who designed Paris Opera) dramatically transformed Casino de Monte Carlo. The result: sumptuous Baroque decoration and the Salle Garnier opera house completed 1892. By 1869, casino revenues allowed Prince Charles to abolish taxation entirely in Monaco.

Henri Negresco commissioned architect Édouard-Jean Niermans to build a hotel surpassing all rivals. Hotel Negresco opened January 1913, with white façade and pink dome overlooking the Bay of Angels. The Royal Lounge’s Baccarat chandelier was originally commissioned by Czar Nicholas II. The first season earned 800,000 gold francs, attracting Vanderbilts, Queen Amelia of Portugal, and Russian Grand Dukes.

When World War I erupted, Negresco opened his hotel as hospital. By war’s end he was ruined, dying in Paris in 1920. The hotel declined until 1957, when the Augier family purchased it. It received National Historic Building status in 2003.

The Carlton Cannes opened in 1913, becoming “La Grande Dame” of Cannes and achieving fame during the annual Film Festival. Artists including Auguste Renoir, who built his estate in Cagnes-sur-Mer in 1907, were drawn by climate and luminous light.

Gerald and Sara Murphy Invented Summer

The revolutionary insight came from wealthy American expatriates. Gerald Murphy, heir to Mark Cross luxury goods fortune, and wife Sara moved to Paris in 1921. In summer 1922, they visited Cole Porter in Antibes. The Murphys fell instantly in love with the deserted summer Riviera.

In 1923, they convinced the Hôtel du Cap owner to remain open through summer (previously, Riviera hotels closed every May). They purchased Villa America in Cap d’Antibes and, with Cole Porter, began raking seaweed from La Garoupe beach, uncovering sand. They introduced sunbathing as fashionable activity, revolutionary when tans signified peasant labor.

The Murphys brought Pablo Picasso to Antibes that first summer. Their circle expanded to include the Fitzgeralds, Hemingway, Dorothy Parker, Jean Cocteau, and Lost Generation luminaries. They entertained with spectacular parties, invented cocktails, wore creative attire, and played jazz at the beach. Their lifestyle launched summer on the Riviera.

Tender is the Night Immortalized Paradise

0

Artists Claimed the Light as Muse

Pablo Picasso first visited in 1923 with the Murphys. He worked at Château Grimaldi in Antibes in 1946 (now Musée Picasso), then moved to Vallauris from 1948-1955, creating hundreds of ceramic works. His final decade was spent in Mougins, where he died in 1973.

Henri Matisse first came to Nice in 1917, moving permanently by 1921, remaining until death in 1954. He designed the Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence from 1947-1951, creating stained glass and mural ceramics. The Musée Matisse in Nice (opened 1963) houses one of the world’s largest collections of his work.

Marc Chagall settled in Saint-Paul-de-Vence in 1966, remaining until death in 1985. The Musée National Marc Chagall in Nice (opened 1973) displays his Biblical Message cycle.

Grace Kelly's Wedding Defined Postwar Glamor

The first Cannes Film Festival opened September 1946, after 1939 cancellation when Hitler invaded Poland. Held at the Casino of Cannes, it marked French cinema’s return to world screens. The Palme d’Or award was introduced in 1955.

Grace Kelly met Prince Rainier III on May 6, 1955, during a photo session at Monaco’s Palace. She was at Cannes for the Film Festival, having won Best Actress Oscar for “The Country Girl.” After correspondence, Rainier proposed Christmas 1955.

The civil ceremony occurred April 18, 1956, in the Throne Room with 80 guests. The religious ceremony followed April 19 at Saint Nicholas Cathedral with 700 guests including Cary Grant, Ava Gardner, and Aristotle Onassis. Over 30 million viewers watched on television across nine networks, the “wedding of the century.”

Designer Helen Rose created the gown with 25 yards of silk taffeta, 100 yards of silk net, thousands of pearls, and 125-year-old lace. The wedding generated massive media attention, establishing the Riviera as epitome of glamor and romance.

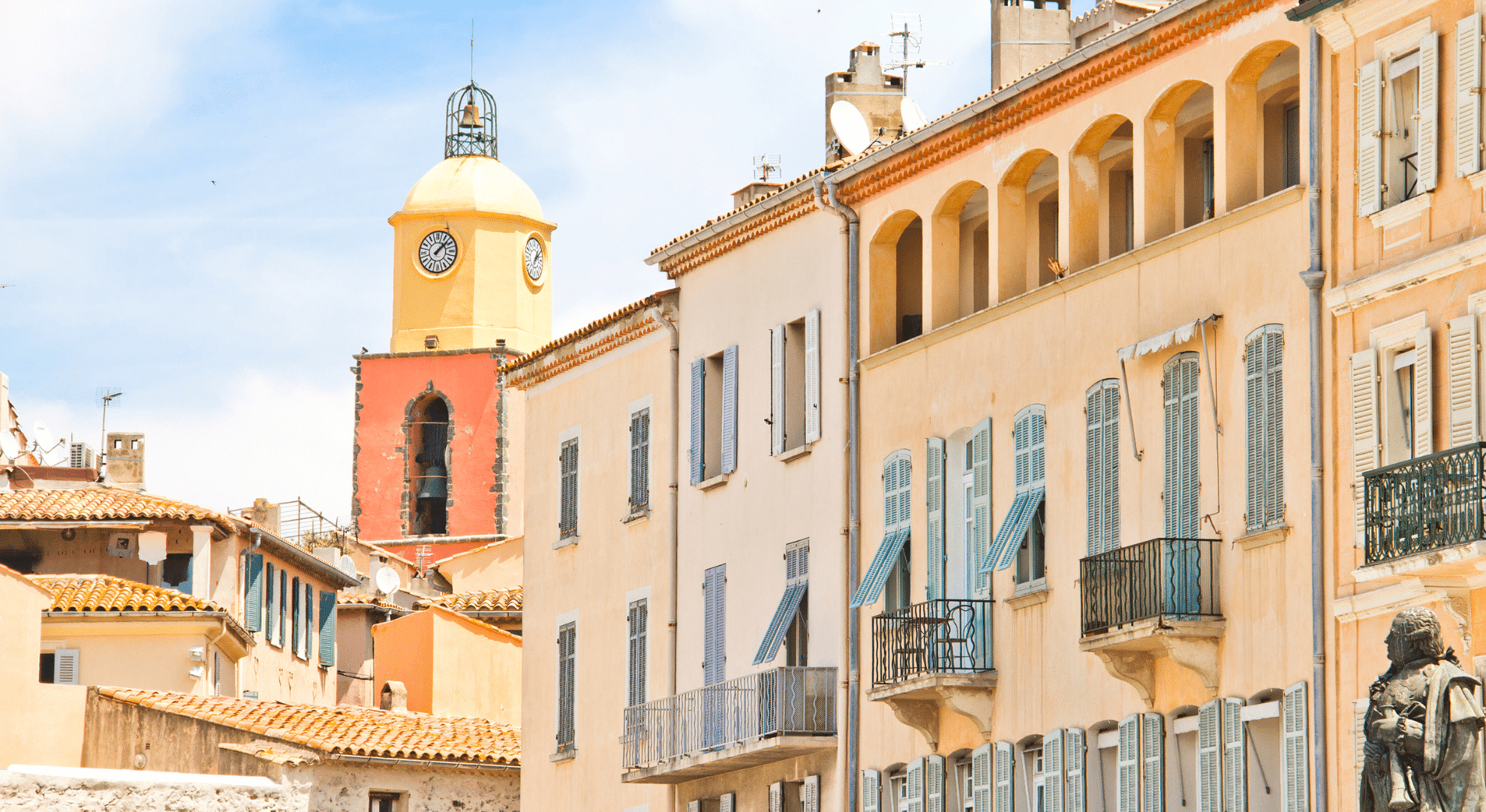

Bardot Transformed Saint-Tropez

In 1956, director Roger Vadim filmed “And God Created Woman” in Saint-Tropez, starring Brigitte Bardot as an 18-year-old whose sensuality scandalizes the town. Released November 1956, the film made Bardot an international sex symbol and transformed Saint-Tropez from unknown fishing village to international jet-set destination.

The film scandalized the United States. It popularized the bikini, introduced the “Bardot neckline,” and paved the way for French New Wave cinema. Bardot purchased La Madrague estate in Saint-Tropez, which remains her residence.

The Mythology Persists

The modern Riviera maintains its luxury appeal through strategic preservation. The Cannes Film Festival attracts 30,000 professionals annually. Palace hotels have been renovated while maintaining character. World-class museums preserve artistic heritage: Musée Matisse and Musée Marc Chagall in Nice, Musée Picasso in Antibes, Musée Renoir in Cagnes-sur-Mer.

Modern superyachts congregate during Monaco Grand Prix and Cannes Film Festival. The Monaco Grand Prix, established 1929, remains a Formula One highlight. Fashion houses leverage Riviera mystique. Real estate in Cap d’Antibes and coastal areas remains among the most expensive globally.

The Riviera has evolved from exclusive winter health resort for British aristocracy to year-round destination welcoming both elite travellers and middle-class tourists, yet remarkably maintains its reputation for luxury, beauty, and cultural significance.

The transformation from impoverished fishing villages to the world’s most glamorous coastline represents not just tourism success but cultural mythology. Each generation discovered anew what previous visitors established, believing themselves pioneers while following well-trodden paths. The Riviera’s genius lies in perpetual reinvention while maintaining core identity: sun-drenched beauty, accessible luxury, creative inspiration, and the persistent belief that something magical awaits around the next cove.

Book your French Riviera escape with Do Not Disturb and travel where history and luxury intertwine.

Related destinations

Suggested articles

A Day in Marseille: Street Art, Bouillabaisse, and the Côte d’Azur

Nice or Marseille: Which Is Better?

What to Know Before Visiting Facteur Cheval’s Palace in France

How to Plan a Wine Tasting Trip in France

Plan Your Honeymoon in Saint-Tropez

How to Plan the Perfect Luxury Trip to Angkor Wat

A Guide to Sri Lanka’s Tea Plantations

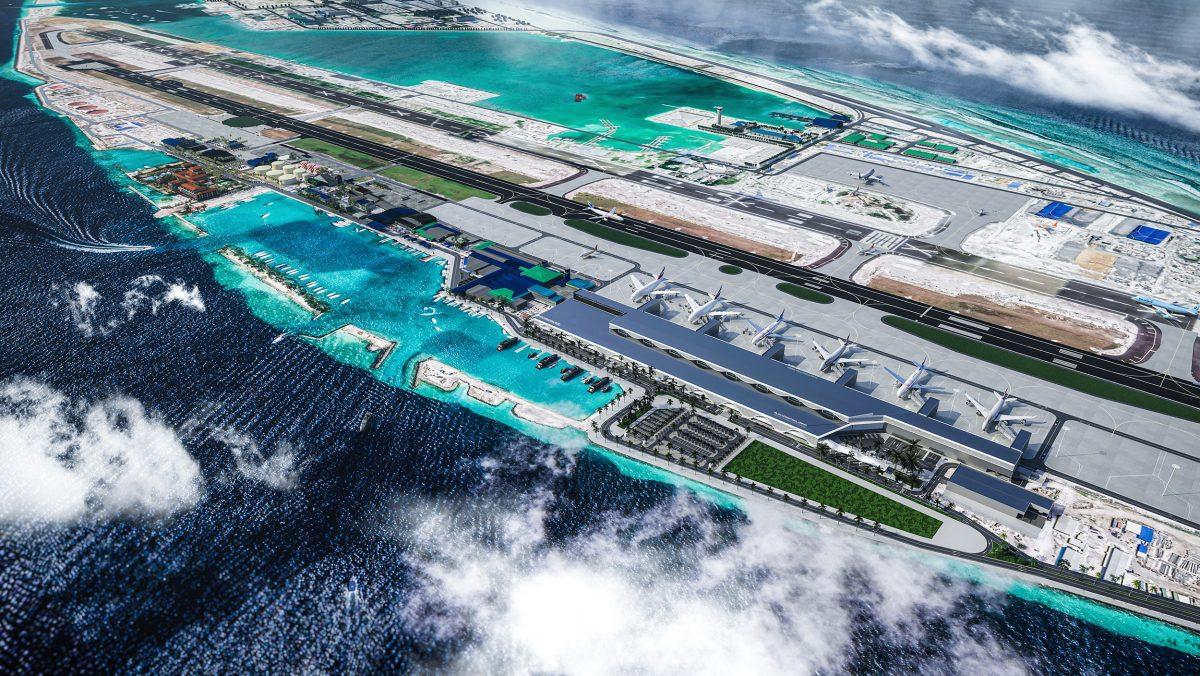

The Maldives Fixed Its Arrival Problem: Inside the New Velana Airport

The Best Islands in Australia for a Luxury Beach Holiday

How to Plan a Luxury Australian Outback Experience

A Luxury Guide to Australia’s Wine Regions

How to Plan a Luxury Trip to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef

The Best Luxury Hotels in Seychelles

Best Caribbean Islands for Private Jet Travellers